Eleven mummies, found by Lebolo were eventually sent to the United States, four of which were purchased by the church in Kirtland in 1835. The history of the mummies was published in a church publication in December of 1835. It reads:

The public mind has been excited of late, by reports which have been circulated concerning certain Egyptian mummies and ancient records which were purchased by certain gentlemen of Kirtland, last July… The records were obtained from one of the catacombs in Egypt, near the place where one stood the renowned city of Thebes, by the celebrated French Traveler, Antonio Lebolo in the year 1831. He procured license from Mehemet Ali, then Viceroy of Egypt, under the protection of Chevalier Drovetti, the French Consul, in the year 1828; employed 433 men four months and two days (if I understood correctly, Egyptian or Turkish soldiers), at from four to six cents per diem, each man entered the catacomb June 7, 1831, and obtained eleven mummies in the same catacomb: about one hundred embalmed after the first order, and deposited and placed in niches, and two or three hundred after the second and third order, and laid upon the floor or bottom of the grand cavity, the two last orders of embalmed were so decayed that they could not be removed, and only eleven of the first, found in the niches. On the way from Alexandria to Paris, he put in at Trieste, and after ten days illness, expired. This was in the year 1832. Previous to his decease, he made a will of the whole to Mr. Michael H. Chandler, then in Philadelphia, Pa. his nephew whom he supposed to have been in Ireland. Accordingly the whole were sent to Dublin, addressed according, and Mr. Chandler’s friends ordered them sent to New York, where they were received at the custom house, in the winter or spring of 1833. In April of the same year, Mr. Chandler paid the duties upon his Mummies, and took possession of the same. Up to this time they had not been taken out of the coffins nor the coffins opened. On opening the coffins he discovered that in connection with two of the bodies, were something rolled up with the same kind of linen, saturated with the same bitumen, which, when examined, proved to be two rolls of papyrus, previously mentioned. I may add that two or three other small pieces of papyrus, with astronomical calculations, epitaphs, etc. were found with others of the Mummies.1

Concerning the discovery, we must rely on sources that are not even second hand. According to the Chandler/Cowdery account, it states that the records and mummies came from the area of Thebes and were discovered by Antonio Lebolo. There is no question that this is possible, since Lebolo worked almost exclusively in the vicinity of Thebes. He also carried out excavations on his own as is seen with the Soter find and probable others.2

As to the date, there is a problem. I am unaware of any record of Lebolo being in Egypt after December of 1821. Balboni, Gl’Italiani nella Civilta Egiziana, 307, 308. Balboni, in his book has a copy of a letter written by Lebolo to Segate, dated November 25, 1821, Lebolo being in Egypt at that time. Lebolo’s marriage record is dated June 12, 1824 at Venice. The record states, “…born in Castellamonte…presently domiciled in Alexandria Egypt” (H. Donl Peterson, “Mummies and Manuscripts,” 1980). This does not mean in any way that he could not have been or would not have been in Egypt any number of times after 1821.

Dawson, in his Who Was Who, states that Lebolo died in Trieste in 1823. The second edition leaves the death date open in light of Cowdery’s account above.”‘3 However, this is not possible since the church register in Castellamonte records Lebolo’s death there on February 19, 1830.’4 Was Chandler mistaken on the death date? Was he misinformed? Was it Lebolo at all that discovered the tomb? The date for the discovery by Lebolo himself is wrong; of this, there is no doubt. Even if the discovery took place on “June 7, 1831” as stated by Chandler/Cowdery, the time allowed to accomplish all that the report indicated would be questionable.5 Although we can only make assumptions about the difference in dating, other details that Chandler gave about the mummies incline us to question his veracity.

“He procured license from Hememet Ali.” This would have had to have been done in order to “personally” excavate in Egypt at that time. If Lebolo was acting as an independent, he would need a license from Ali. However, if he were operating as an agent of Drovetti, “with permission to ascertain a personal collection,”7

The license was procured by Lebolo, according to Chandler/Cowdery, in 1828. This very well could have been if Lebolo had returned to do excavations on his own.

The report then speaks of Lebolo employing 433 men, four months and two days (such exact numbers!). This is not hard to believe in light of Vidua’s comment that Lebolo would sometimes have up to “three hundred men at his command.”8 According to this account, after entering the tomb, they obtained eleven mummies; probably those had coffins and could be removed intact. It would be surprising if there were not more than eleven coffins in the tomb, and as habit dictated in the past, the better ones were opening looking for valuable artifacts.”‘9 “One hundred mummies after the first order, and ‘one to two hundred after the second and third order’ were contained in the tomb.” Of the two to three hundred mummies in the tomb, most were in such a state of decay that only eleven could be removed. As Henniker stated, there were more than fourteen mummies in the Soter tomb and all but those fourteen were too decayed to be removed.”10

Belzoni speaks of such a tomb as described by Chandler/Cowdery:

After the exertion of entering into such a place, through a passage of fifty, a hundred, three hundred, or perhaps six hundred yards, nearly overcome, I sought a resting-place, found one, and contrived to sit; but when my weight bore on the body of an Egyptian, it crushed like a bandbox. I naturally had recourse to my hands to sustain my weight, but they found no better support; so that I sank altogether among the broken mummies, with a crash of bones, rags, and wooden cases, which raised such a dust as kept me motionless for a quarter of an hour, waiting till it subsided again. I could not remove from the place, however, without increasing it, and every step I took I crushed a mummy in some part or another. Once I was conducted from such a place to another resembling it through a passage of about twenty feet in length, no wider than body could be forced through. It was choked with mummies, and I could not pass without putting my fact in contact with that of some decayed Egyptian; but as the passage inclined downwards, my own weight helped me on; however, I could not avoid being covered with bones, legs, arms, and heads rolling from above. Thus, I proceeded from one cave to another all full of mummies piled up in various ways some standing, some lying, and some on their heads. The purpose of my researches was to rob the Egyptians of their papyri; of which I found a few hidden in their breasts, under their arms, in the space above the knees, on the leg, and covered by numerous folds of cloth that envelop the mummy.11

It is possible that this large number of mummies could have been in the tomb with the eleven that Chandler received. However, there is one problem. There are not that many known tombs in Qurna that could accommodate two or three hundred living, much less mummified, people. Could the eleven mummies that Chandler received have come from more than one tomb? Could they derive from Lebolo’s last collection, sold after his death?

Lebolo did not make a will leaving the eleven mummies to Michael H. Chandler. The will of Antonio Lebolo was found in the fall of 1984 and contained no mention of a Michael H. Chandler, or the eleven mummies. The will itself was over two hundred pages, most of which listed Lebolo’s belongings. From his will, Lebolo obviously passed away a wealthy and influential man in his community.12

Where then did the eleven mummies that Michael Chandler acquired from? At the time the will was found, and in the same archives, the heirs of Antonio Lebolo were filing suit against one Alban Oblasser, dated July 30, 1831. This suit charged Oblasser, who then resided in Trieste, of the sale of “eleven mummies” that he had been given by Lebolo to sell on consignment. The sale of these mummies by Oblasser left monies owing the estate of the Lebolo heirs.”13 Could these “eleven mummies” be the same “eleven mummies” that Chandler received?

Another account of Chandler receiving the mummies is giving in 1842 by P. P. Pratt.

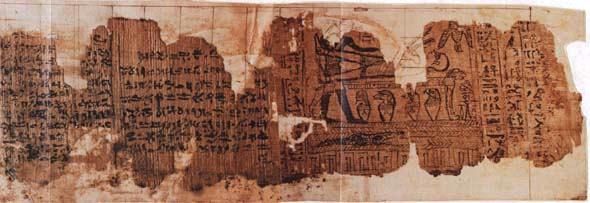

A gentleman, travelling in Egypt, made a selection of several mummies, of the best kind of embalming, and of course, in the best state of preservation; on his way to England he died, bequeathing them to a gentleman of the name of Chandler. They arrived in the Thames, but it was found the gentleman was in America, they were then forwarded to New York and advertised, when Mr. Chandler came forward and claimed them. One of the mummies, on being unrolled, had underneath the cloths in which it was wrapped, lying upon the breast, a roll of papyrus, in an excellent state of preservation, written in Egyptian character, and illustrated in the manner of our ingraving, which is a copy from a portion of it. The mummies, together with the record, have been exhibited, generally, throughout the States, previous to their falling into our hands.14

In light of the “Oblasser suit,” this account seems even more plausible than the Chandler/Cowdery “will” story.

However Chandler came by the mummies, in “April of 1833” he paid the duty and took possession of them. From New York “he took his collection to Philadelphia, where he exhibited them for a compensation.” Cowdery continues, “from Philadelphia he visited Harrisburgh, and other places east of the mountains.” Newspaper accounts and advertisements verify that Chandler did exhibit his collection. A Philadelphia newspaper contained the following:

EGYPTIAN MUMMIES

The largest collection of EGYPTIAN MUMMIES ever exhibited in this city, is now to be seen at the Masonic Hall, in Chestnut Street above Seventh. They were found in the vicinity of Thebes, by the celebrated traveler Antonio Lebolo and Chevalier Drovetti, General Consul of France in Egypt. Some writings on Papirus [sic] found with the mummies, can also be seen, and will afford, no doubt, much satisfaction to Amateurs of Antiquites. Admittance 25 cents, children half price. Open from 9 A.M. till 2 P.M., and from 3 P.M. to 6. Ap 3 – d3W This article began on April 3rd and ran for three weeks.15

The Hartford Republican ran this note while the mummies were on exhibition in Philadelphia: “Nine mummies, recently found in the vicinity of Thebes, are now exhibiting at the Masonic Hall, Philadelphia.”16

By this time two mummies were already missing from the collection of eleven. In Pratt’s account above, Chandler opened one coffin and unrolled one mummy at the customs house. Cowdery, in speaking of this incident, says: “When Dr. Chandler discovered that there was something with the Mummies, he supposed, or hoped it might be some diamonds or other valuable metal, and was no little chagrined when he saw his disappointment.””17 As noted above, one mummy may have been destroyed at the customs house while Chandler searched it for the gold of the Pharaohs. Two mummies appear to have been bought by Samuel George Morton in Philadelphia. He lists in his Catalogue of Skulls under item numbers 48, 60, “48. Embalmed head of an Egyptian girl, eight years of age, from the Theban catacombs. Egyptithan form, with a single lock of long fine hair.18 Dissected by me before the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, December 10, 1833.” There is little question that this mummy came from the Chandler mummies. Entry number 60 leaves no doubt: “Embalmed head of an Egyptian lady about 16 years of age, brought from the catacombs of Al Gourna, near Thebes, by the late Antonio Lebolo, of whose heirs I purchased it, together with the entire body; the latter dissected before the Academy of Natural Sciences, on the 10th and 17th of December, 1833, in the presence of eight members and others. Egyptian form, with long fine hair.”

By the time Chandler reached Baltimore, the number of mummies had dwindled to six. We read: “P.S. The citizens are respectfully informed that the Manager has received from the vicinity of Thebes that celebrated city of Ancient Egypt, Six strangers illustrious from their antiquity, count probably an existence at least 1,000 years anterior to the advent of our blessed Savior…”19

On September 9, 1833, we see in the Harrisburg Chronicle: “SIX EGYPTIAN MUMMIES now exhibiting in the Masonic Hall, Harrisburg.” By the time Chandler reached Cleveland in 1835, he was tired of “life on the road.” Following the typical advertisement of the mummies we read: “The collection is offered for sale by the Proprietor.”20 About three months later, they were bought by the church in Kirtland, Ohio. In the journal of Joseph Smith, it reads for the date of July 3, 1835: “On the 3rd of July, Michael H. Chandler came to Kirtland to exhibit some Egyptian mummies. There were four human figures, together with some two or more rolls of papyrus covered with hieroglyphic figures and devices.”21 On the 6th of July “some of the Saints at Kirtland purchased the mummies and papyrus.”22 Joseph Smith then kept the mummies and papyrus in his possession until his death in 1844. They then passed to his mother who kept them until her death in 1855. Eventually it appears that they were acquired by the Woods Museum in Chicago. After the great Chicago fire of 1871, it was believed that the mummies and papyrus had been destroyed. In 1966, some fragments of the Joseph Smith Papyri were found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, hinting that perhaps at least some of this Lebolo collection may still be found. The church obtained ownership of the eleven fragments of papyri in November of 1967. They are now housed in the Church Archives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Messenger and Advocate, 2:3 (December, 1835); 232-33. This was recorded by Oliver Cowdery, who interviewed Michael H. Chandler within six months of the purchase.

- It would be naive to assume that Lebolo did no digging on his own, or did no more than the Soter excavation, when considering Lebolo sold his own collections to the Vatican and to Burghart for the Imperial Museum of Vienna.

- Dawson and Uphill, Who Was Who, 166. Speaking of the mummies Uphill states that “Further ones appear to have been received in America…which if correct shows that Lebolo cannot have died in 1823 as previously thought.”

- A copy of Lebolo’s death entry is in the position of H. Donl Peterson. It reads: “1830 Lebolo Antonio the wife of whom is Anna Dufour, African woman, son of Pietro and Marianna Meuta, aged of fifty years, provided with sacraments, died on the nineteenth day of February and the next day buried.

- If the discovery took place in June of 1831, the mummies would then have to be removed and transported from Qurna to Cairo, and from there to Alexandra. Once there, they would have to be packed and crated for the voyage to Trieste where they would need to be unloaded and moved to where Lebolo was to die. Once the will was probated (and the freight paid), the mummies were then to proceed to Ireland. After the search for Michael CHandler failed, his “friends” sent them to New York. From the date of entering the tomb to the time Chandler recieved the mumies was about twenty-two months. It is possible, but not probable.

- “Marro Papers.” Marro’s summary of Lebolo. See note 8 above. he would need no license, but would then be “under the protection of” Drovetti.°6 Vidua, in letter No. 34, writes that even the “Turkish commander respects him (Lebolo) for fear of Mr. Drovetti.”

- Ibid.

- Henniker, Notes, 137. See notes 30 and 31 above.

- Ibid.

- Mayes, The Great Belzoni, 160.

- The will is housed in the state archives in Torino. Mr. Comollo, H. Donl Peterson and myself were in Torino for the purpose of locating the will when it was found. Copies of the will are in the possession of Professor Peterson and myself.

- A copy of this suit is in the possession of H. Donl Peterson as well as myself.

- The Latter-Day Millennial Star, 3:3 (July, 1842), 46.

- U. S. Gazette, published by Joseph R. Chandler, Philadelphia, Wednesday, April 3, 1833, p. 3.

- The Hartford Republican, Belle Air, Hartford County, Maryland, 3:41 (Thursday, May 23, 1833):1.

- Messenger and Advocate, p. 234.

- Samuel George Morton, Catalogue of Skulls, (Philadelphia: Merrihew and Thompson, 1849), 38, 39. Both of these mummies were from Thebes and were dissected the same day by Morton.

- American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, Baltimore, July 22, 1833. This article was under the section for the Baltimore Museum and ran through August 9, 1833.

- Cleveland Advertiser, Cleveland, Ohio, Thursday, March 26, 1835.

- Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret, 1973), 2:235.

- Ibid., p. 236.